Alfred Hitchcock

by -- Preston Neal Jones

by -- Preston Neal JonesUniversally acknowledged as "The Master of Suspense," the British-born film director Alfred Hitchcock reached the zenith of his accomplishments within the American film industry, with a series of now classic psychological thrillers that remain a constant presence in the cultural landscape of the moviegoer. Regarded as one of the major artists of Hollywood's Golden Age, Hitchcock created and perfected his own genre of thriller, one which was by turns romantic, comedic, and macabre, and his unique gift for creating suspense has given the adjective "Hitchcockian" to the language. A supreme cinematic stylist, it was said of him that he filmed murder scenes as if they were love scenes and love scenes as if they were murder scenes. Thanks to his hosting of Alfred Hitchcock Presents during the 1950s, he became probably the only film director whose face was recognisable to the general public, although, master showman that he was, he made a fleeting trademark appearance in virtually every one of his films, giving audiences the added frisson of trying to spot him on the screen. His mastery of film technique, refined in the silent era, combined with his ability to, as he put it, "play the audience like an organ," made his films extremely popular -- so popular, in fact, that the respect of his critics and peers was not immediately forthcoming. Today, however, his place in the cinematic pantheon is secure, and his work continues to exert an overwhelming influence on upcoming generations of film-makers. For better or worse, Hitchcock's most lasting impact may prove to have been the floodgate of still-escalating violence which he unleashed on screen in his 1960 masterpiece, Psycho.

Alfred Joseph Hitchcock was born in suburban London on August 13, 1899. Raised in a Catholic household by an emotionally repressed father, he was a painfully shy child. Years later, he would often repeat the story of how his father had instructed the local police to place the boy in a cell for a short time in order to demonstrate what happens to bad little boys who misbehave. A recurring theme of his films is a fear of the police. Young Hitchcock developed an interest in art, but his first job was as a technical clerk in a telegraph company. In 1919, he joined the Islington branch of the Famous Players Lasky film company as a designer of title-cards. He was hired as an assistant director for the production company run by Michael Balcon and Victor Saville in 1923, where he met Alma Reville, a petite film editor whom he married three years later. Reville would remain Hitchcock's collaborator and confidante for the remainder of his life. After starting to write scripts, Hitchcock was sent to work on a German-British co-production at the UFA studios, famous home of the German Expressionist cinema, which would eventually reveal its influence in his own work.

By 1925, he had worked on half-a-dozen British silents in various capacities as assistant director, art director, editor, and co-scriptwriter. That year he directed his first solo feature, The Pleasure Garden, but it was his third, The Lodger (1926), that began to earn him his early reputation. Starring the British composer of "Ruritanian" musical romances and matinee idol of the musical stage, Ivor Novello, the tale concerned a mysterious stranger wrongly thought to be Jack the Ripper. Many years later, Hitchcock said of the film, "It was the first time I exercised my style ... you might almost say it was my first picture." He only returned to the thriller form six pictures and three years later with Blackmail, the first British talkie or, more accurately, part-talkie (it had begun shooting as a silent). Alternating thrillers with "straight" pictures for a time, Hitchcock truly hit his stride in 1934 with The Man Who Knew Too Much, a fast-paced story of kidnapping and espionage, filled with memorable set-pieces such as the assassination attempt during a concert at Albert Hall. He remade it in 1956 starring James Stewart, Doris Day, Vistavision and the song "Que Sera Sera" but despite its massive box-office success, critics continue to agree that the early version was the more refined and effective.

The Man Who Knew Too Much launched what is now referred to as Hitchcock's "British period," in which he turned out one successful thriller after another, notably The Thirty-Nine Steps (1935) and one of the most famous of British films, The Lady Vanishes (1938). The former, one of several screen versions of John Buchan's novel, starred Robert Donat and Madeleine Carroll, and set the tone for many Hitchcock classics to follow, in its combination of comedy, action, and romance, and its theme of an innocent man hounded by the police as well as the arch-villains. Though it would take a generation for the more intellectual film critics to catch up with the public which made these movies hits, Hitchcock's films were remarkable for the craft with which they so skillfully hooked audiences and kept them in suspense for an hour and a half. The director paid immaculate attention to working out every detail, and often claimed that, with the script and storyboard complete, the actual filming itself was an anti-climax. He called upon the fullest vocabulary of cinema, from casting and camera-work to editing and sound, to tell his stories, and was a great believer in the power of montage, which he employed masterfully.

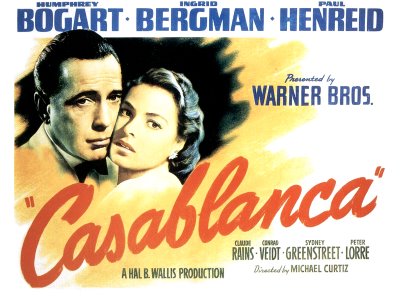

Inevitably, Hollywood beckoned, and Hitchcock signed a contract with producer David O. Selznick. Their first collaboration, Rebecca (1940), from the novel by Daphne Du Maurier and starring Joan Fontaine and Laurence Olivier, was largely British in flavor, but won Hitchcock the first of his five Academy nominations for Best Director, seven additional nominations (including one for Judith Anderson's immortal Mrs. Danvers) and carried off the Best Picture and Cinematography Oscars. Rebecca was an unqualified triumph, but Hitchcock chafed under the oppressively hands-on methods of his producer, and yearned for artistic independence. Meanwhile (sometimes on loan-out to other studios), he directed American films that continued his cycle of spy-chase thrillers but, in keeping with the World War II years, cunningly carried anti-Nazi propaganda messages as in Foreign Correspondent (1940, with Joel McCrea in the title role as an American war correspondent tangling with Nazi thugs), Saboteur (1942, with Robert Cummings tangling with Fifth Columnists), Lifeboat (1944, with Tallulah Bankhead and others surviving a German torpedo and seeking safety), and Notorious (1946), the second of three with Ingrid Bergman and four with Cary Grant, who infiltrate a group of Nazi conspirators in South America in one of the director's most stylish thriller-romances.

Sometimes cited by Hitchcock as his personal favorite, Shadow of a Doubt (1943), which starred Joseph Cotten as a killer escaping detection by "visiting" his adoring relatives, brilliantly dramatized the terrors that can lurk in the shadows of a seemingly normal small town. It was this penchant for perceiving the disturbance underneath the surface of things that helped Hitchcock's movies to resonate so powerfully. Perhaps the most famous demonstration of this disjunction would come in North by Northwest (1959), where Cary Grant, seemingly safe on a sunny day, surrounded by miles of empty farm fields, suddenly finds himself attacked by a machine-gunning airplane. Before the rich collection of war years thrillers, there was a beguiling and polished foray into domestic comedy drama with Mr. and Mrs. Smith (1940, with Carole Lombard and Robert Montgomery) and the romantic and sophisticated suspense tale Suspicion (1941, Grant and Fontaine), which pointed the way toward Hitchcock's fertile 1950s period.

The postwar decade kicked off with the adaptation of Patricia Highsmith's novel Strangers on a Train (1950), in which Farley Granger and Robert Walker swap murders. The film climaxed with one of Hitchcock's most famous and memorable visual set pieces, a chase in a fairground. It was filmed in black and white, as was I Confess (1952, with Montgomery Clift as a priest who receives an unwelcome confession). To date, the Master of Suspense had only ventured into color twice (Rope, 1948, and, one of his rare failures, Under Capricorn, 1949). Now, he capitulated to color for the remainder of his career, with the well-judged exceptions of the Henry Fonda vehicle, The Wrong Man (1956), and his most famous film, Psycho. Along with color, his taste for blonde leading ladies took on an almost obsessional aura and led, during the 1950s, to films with Grace Kelly, Doris Day, Eva-Marie Saint, Kim Novak, Janet Leigh, Julie Andrews, and, famously in The Birds (1963) and then in Marnie (1964), the previously unknown Tippi Hedren (whose career swiftly petered out thereafter).

His professional reputation secure, Hitchcock gained his artistic independence and entered a high period in which he turned out success after success, some better than others, but all of them entertaining. However, along with North by Northwest, which saw out the 1950s, the two masterpieces of the decade emerged from his three-picture collaboration with James Stewart, and marked a new dimension of interior psychological darkness that, in each case, infused every frame of an absorbing plot line. The films were, of course, Rear Window (1954) and Vertigo (1958), both of which dealt with obsession under the deceptive guise of a straightforward thriller. The first, with Stewart laid up with a broken leg and witnessing a murder across the way as a result of spying on his neighbors by way of a pastime, hinted at voyeurism; the second, in which he turns the lookalike of an illicit dead love into an exact copy of her predecessor (both played by Kim Novak), deals in guilt and sick delusion. Vertigo, for sheer artistic expertise, combined with Stewart's grim, haunted performance and the disturbing undertones of the piece, is quite possibly the most substantial of the postwar Hitchcock oeuvre, but the public impact of his first for the new decade capped all of his recent accomplishments.

The director's first excursion into unabashed horror, Psycho (1960) sent shock waves which continue to reverberate through the genre. The murder of Janet Leigh in the shower has been imitated, suggested, and ripped off in countless films since, and has become part of the cinema's iconography. In certain cases, such as Dressed to Kill (1980), Brian De Palma made no secret of the fact that he was drawing on the association in open homage to Hitchcock. Psycho (which drew on the Ed Gein multiple murder case for its inspiration) caused much controversy on its release, and has since been analyzed endlessly by film historians and academics. When a shot-by-shot color remake by Gus Van Sant, made ostensibly as the highest form of compliment to the original, emerged late in 1998, a rash of fresh argument was unleashed as many bemoaned the pointlessness of the exercise or, indeed, the travesty that many considered it to be. The original is generally considered as Hitchcock's last great film, attracting additional reverence for the contribution of his frequent collaborators Bernard Herrmann (who composed the pulsating score) and Saul Bass, the great designer of opening titles. Several of the Hitchcock masterpieces owe a debt to these two creative artists, and the Bass titles for Vertigo remain a work of art in their own right.

The follow-up to Psycho, The Birds (1963) was less highly regarded, but is a durable and complex experiment in terror, and a monument to technical expertise. In the late 1990s it, too, became the subject for renewed examination and analysis, notably by the controversial feminist academic Camille Paglia, who admired it greatly. There were only five more after The Birds--a varied quintet that signaled a decline in the director's prodigious powers--and he bowed out, somewhat disappointingly it has to be said (but he was, after all, 77 years old), with Family Plot in 1976. By then, however, thanks to TV's Alfred Hitchcock Presents, he had cemented his image in the public consciousness as the endearingly roly-poly master of dryly witty gallows humor. In his later years, Hitchcock had the pleasure of being lionized by the newer generations of film-makers, and the wistful experience of attaining honors which long earlier should have been his. Although, inexplicably, he never won an Oscar for directing, the Academy did ultimately honor him with the Irving Thalberg Award in recognition of his work, and he was also made the recipient of the American Film Institute Lifetime Achievement award.

St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Culture, 2002 Gale Group.